Image Source: Yury Kim

If someone is hurt on the job, they are entitled to worker’s compensation, regardless of socioeconomic status, thanks to the Occupational Safety and Health Association (OSHA).

But are there people more likely to get hurt in the first place?

The CDC’s Health Disparities and Inequalities Report (CHDIR) provides some insight into this question that could suggest the answer is yes. According to the report’s section on fatal work-related injuries:

“Hispanics and foreign-born workers had the highest work-related fatal injury

rates (4.4 and 4.0 per 100,000 workers, respectively).”

In addition to this, the report notes that although Hispanic and foreign-born workers had the highest on-the-job fatality rates overall, ‘non-Hispanic blacks’ had either the highest or second highest fatality rates in many industry categories. So, is there a connection?

The U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics suggests that the majority of ‘high risk jobs’ (first responders, construction, heavy equipment operation, etc.) are not heavily populated by any specific race. That is to say, there is not a clear connection between minorities and being forced into high-risk careers. So why do the majority of on-the job deaths not include white workers?

The answer to the connection between race and an increased rate of death by on-the-job accidents could be from a variety of involved factors. It may be possible that the cause of increased fatality lies in the continued systematic oppression of non-white workers – meaning that minority employees in dangerous jobs may be worse off both health-wise and financially than their white co-workers.

An article about the connection between demographics and work injuries supports this idea by noting workers from ‘minority’ backgrounds face many more hazards than their white counterparts.

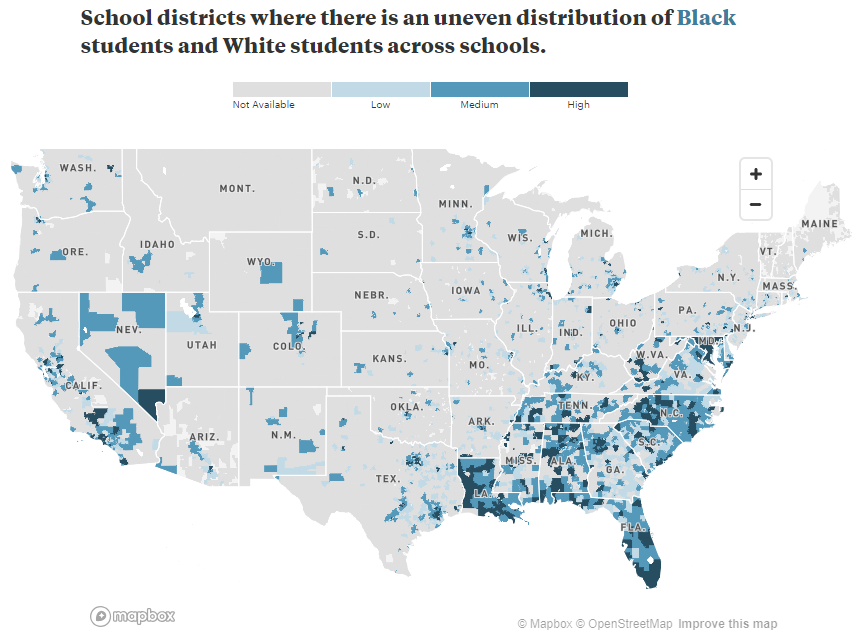

Avoiding these hazards that reduce quality of life for many individuals seems to be unfortunately unavoidable. Poverty among non-white individuals persists for generations due to systematic oppression and continually forces workers into less ‘educated’ professions due to lack of educational resources and discrimination, preventing them from breaking the cycle of abuse.

A 2013 report by Liana Christin Landivar notes that typically high-paying STEM careers are populated almost exclusively by white and Asian employees, and additionally notes a noticeable disadvantage to black or Hispanic students looking to get into the field, especially if they are women.

With no opportunity to get ahead and consistent challenges not faced by white employees, it becomes apparent that Hispanic and black employees in high-risk careers face many struggles that others do not. Their increased risk of fatality in the workplace, therefore, can be observed to be another deeply negative aspect of systematic oppression.

With higher rates of incarceration, a mishandling of ‘high risk youth,’ poor healthcare access, unfair housing practices, and many other factors, the case for racially-motivated disadvantage in the workplace is clearly evident.

With the odds overwhelmingly stacked against them, the connection between socioeconomic status, ‘class,’ and race and a higher chance of being injured at work does in fact seem to be a legitimate issue worth investigation.